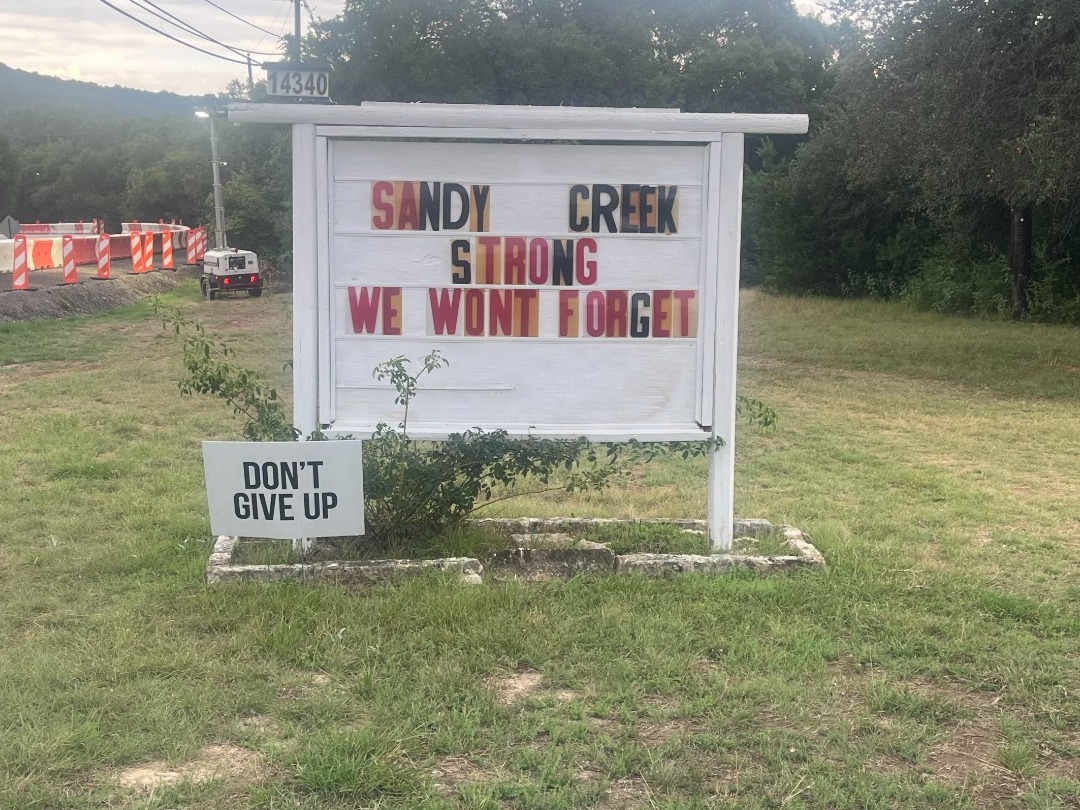

Washed out: Sandy Creek residents fault official flood response

The July floods that hit Central Texas were catastrophic, killing more than 135 people, including 27 campers and counselors at Kerr County’s Camp Mystic and 10 people near Leander in Travis County. Estimated damages are approximately $20 billion.

As residents and officials continue assessing damages, a critical deadline is approaching for impacted residents to apply for assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. They have until Sept. 28 to apply.

In recent interviews, several flood survivors told Austin Free Press that there are lingering questions and challenges in the aftermath of the disaster. Many Central Texas families said they still are dealing with the trauma of what unfolded that cataclysmic day in July and looking for answers, which at best, have been slow to come.

“It’s usually a dry creek bed,” said Kaleena Schumaker, whose family has lived along Big Sandy Creek near Leander for half a century.

Schumaker said she woke up at 2:35 a.m. on the morning of July 5 as water inundated her property. She went to the back of the house — facing Big Sandy Creek — to release her herd of goats to seek higher ground.

“They were already gone,” she said. “Swept away.”

Schumaker and at least nine other family members all evacuated by driving up to the safety of a neighborhood hill.

“I pulled into a community member’s driveway and just started honking the horn,” she said.

As floodwaters raged, residents began conducting search and rescue efforts for neighbors who were unaccounted for.

“We were searching for our own friends and family,” Schumaker said. “It happened by word of mouth. Some knew a community member’s home was swept away, so they hit the water with their own boats and went searching.”

In all, Travis County reported that the flooding caused 10 deaths and damaged more than 200 homes near Sandy Creek.

County overwhelmed?

Months after the disaster, impacted residents still are questioning the county’s response to flooding, including whether it was timely enough – a view that county officials say overlooks their efforts.

Schumaker said she didn’t see any county or emergency officials in her neighborhood until 11 to 12 days after the flooding. Volunteers began clearing the debris along the bridge before the county did, Schumaker said. “It was 100 percent all volunteers,” she said. “They came with chainsaws but quickly saw that heavy equipment was needed.”

Lisa Ross, a 17-year resident of Big Sandy Creek, said she also noticed the lack of emergency personnel responding to the flood as she drove out to alert friends living along Windy Valley Road before dawn on July 5.

“It was 3 o’clock, and residents were helping each other get out of their houses,” she said. “I did not see an emergency response crew. What I saw was a lot of neighbors helping neighbors.”

Travis County Judge Andy Brown defended the county’s response, telling state lawmakers at a July 31 hearing that the county and Texas Division of Emergency Management mobilized every available resource starting on July 5. Brown acknowledged, however, that communication gaps may have prevented residents from knowing what officials were doing immediately following the flooding.

Within 24 hours of the flood, residents said that volunteers streamed into the Big Sandy area to clear debris. The flood severely damaged Sandy Creek Bridge, making the only access point in and out of Schumaker’s neighborhood impassable.

Sandy Creek Bridge was only accessible to foot traffic for nine days before Travis County completed a temporary, low-water vehicle crossing that opened on July 14.

Travis County Director of Public Information Hector Nieto said that a contractor has been selected to repair the flood-damaged bridge, which could take up to 40 days.

Troubled waters

Despite the creation of a temporary shuttle service, residents had trouble accessing help at disaster resource centers initially set up at Danielson Middle School and then relocated to Round Mountain Baptist Church.

“This wasn’t ideal for people who live at the back of the neighborhoods,” Ross said. “Walking 30 minutes in the sun to catch a shuttle to access resources when you’re elderly or a single mom is tough.”

When the church became inundated with donations, Ross helped organize a closer distribution center at Round Mountain Community Center. Schumaker set up a distribution area in her driveway.

“There’s a lot of poverty here. A lot of elderly people and single parents,” Ross said. “They don’t know how to get past those obstacles.”

Ross said trust between residents and officials is broken. “It’s been very eye opening to see how much the community feels like officials don’t care about us,” she said. “A lot of people are either afraid of unfamiliar faces, or they don’t know about resources available to them.”

With the Sept. 28 deadline looming, some residents find the process challenging — or question some government-aid proposals.

“County engineers have proposed rebuilding homes with piers,” Ross said. “They don’t seem to understand that our elderly community might not be able to access their homes that way.”

Texas requires permits to build in floodplains and mandates that structures be elevated above base flood levels. But rural communities such as Sandy Creek often lack good flood maps or watershed oversight, leaving residents vulnerable.

Future flood plans

The Sandy Creek residents who had to warn each other of rising floodwaters and conduct rescues themselves underscore the wider flood challenges faced by Central Texas’ growing population.

“I’d like to see better communication with the authorities,” Ross said. “Better warnings, better relief organization and a better understanding of the communities that they serve. People need a lot of monetary help right now.”

Texas lawmakers recently approved measures to mitigate and better respond to future flash floods. The new laws set safety measures for youth camps, including prohibiting cabins in floodplains and mandating emergency plans and warning systems. Other steps seek to improve communication among first responders, oversee disaster donations, and punish disaster-related scams.

In a statement, Travis County noted that a long-term recovery group has been formed by Sandy Creek residents and more than 50 groups to help the community its ongoing flood recovery.

The Travis County Commissioners Court and the Central Texas Community Foundation created the Travis County CARES Fund to provide financial relief to those hit by the floods.

Sandy Creek residents said they continue to put more faith in community bonds than in government aid.

“I don’t understand the state, I don’t understand the county, and I don’t understand why,” Schumaker said. “Texans are Texans and we’re going to protect our own.”

This article was originally published on Sept. 23, 2025 on www.austinfreepress.org.

Post a comment